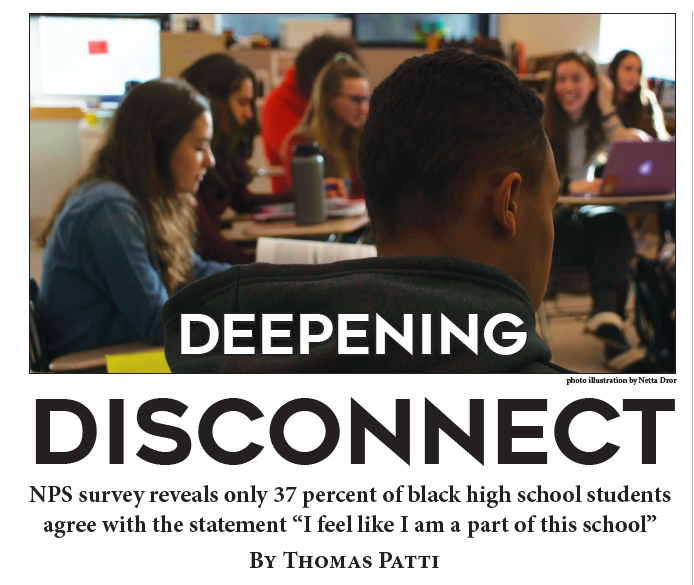

Deepening Disconnect

June 24, 2018

Additional reporting by Michelle Cheng and Carina Ramos

November 14, 2017

Every morning when her school bus turns into South’s parking lot, senior Khyla Turner prepares to adjust her body language and word choice. For the next eight hours, she will assume her second identity: the “Newton South Khyla.” The stark contrast between her home and school environments, she said, necessitates this change of face.

“It’s just different,” she said. “I’m off the bus, I’m in the breezeway now, so I have to do kind of a face-switch. Some things stay the same, but you lose a lot of your identity when you step off that bus.”

Turner, a METCO student and co-president of the Black Student Union, said many students of color feel similarly weary of their image within the South community. In fact, a 2016 citywide survey of seventh to twelfth graders indicates that black students’ sense of disconnectedness from the Newton high schools is on the rise.

According to Newton’s 2016 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), 65 percent of white high school students agreed that they felt connected to their school. Among black high school students, only 35 percent said so — nearly a 20 percent decrease from 2014.

“I wouldn’t say that I was surprised, but I was definitely disappointed,” senior Bennett Walkes, a student facilitator for South’s Courageous Conversations on Race, said of the report. “I think that these results sort of show where our racial climate is at at South. If you’re a student of color, it’s easy to feel sort of isolated in this community, and I think that’s a thing we need to work on.”

Principal Joel Stembridge agreed, acknowledging that the school’s efforts in recent years have met limited success.

“The issue of how students of color are connected to our school is not new,” he said. “It’s one we’ve been thinking about and working on. And to have these numbers go in the exact opposite direction that we want them to go in is concerning.”

Administered every two years since 1998, the YRBS began as part of a national push to address the perceived epidemic of risky behavior among teens. In 2014, the district began analyzing the results to examine possible causes of the achievement gap between black and white students, Superintendent for Teaching and Learning Mary Eich said. By sorting student responses to the statement “I feel like I am a part of this school” by race, she said, the district could begin to evaluate whether minority students’ discomfort in their classrooms might contribute to the gap.

“What we wanted to know, or what we sort of had an idea about, is that black kids don’t necessarily feel as much a part of their school as white kids,” she said. “If that were the case, they might not have the connections with teachers, with each other, with other kids that would support a strong academic performance.”

Increased media coverage of police shootings of unarmed black men the previous summer likely affected students’ responses, guidance counselor Amani Allen said. Turner agreed that there were likely national factors at play.

“Outside of school, in the real world, kids don’t feel like their country or nation accepts them,” she said. “Then they come to school and they feel like it’s more of that.”

According to Stembridge, however, these national issues cannot excuse the district’s poor performance.

“[The question] doesn’t say ‘do I feel a part of my country;’ it says ‘do I feel a part of my school,’” he said. “I would prefer we not explain it away too much, and instead, I really believe that the next step is to invite students who have answered this survey to come and talk and to share their experiences and share why would they say they’re not feeling part of the school.”

The 2016 election has caused an increase in racially insensitive behavior among white Newton students, METCO counselor and African American Literature teacher Katani Sumner said. The survey coincided with an incident in which a group of students drove through a Newton North parking lot with a Confederate flag.

During the spring of 2017, Allen said, displays of hate took center stage at South as well, including racist comments at Multicultural Day and a racial slur directed toward a black student by a white student.

In the locker rooms, students of color face premature accusations of theft when an item goes missing, Turner said, and white students regularly use the N word to address black students.

Junior football player Salim Gomez, who identifies as black and Latino, said he has experienced acts of racism on the field, including from his own teammates during practice. In general, he added, making connections with students of majority races has been difficult.

“When I do try to associate with white or Asian people, there’s really no connection because it can either be the things we talk about are different or the way we talk is different, or just how we feel comfortable talking with each other [is different],” he said. “I don’t think they’re comfortable interacting with me.”

These issues pose a unique burden for students of color in the classroom, Turner said. Microaggressions and unfair judgments, she said, divert students’ attention from their academic achievement.

“I would like my teachers to recognize that in a classroom we’re not just learning material … like all the other students,” she said. “We’re being aware of our person, making sure we don’t fit into those stereotypes 24/7, so it might impact our studies a little more than a white kid or another minority or an Asian student because we’re not only worried about our grades, we’re worried about how people perceive us.”

These constant fears ultimately result in a loss for the entire school community, Sumner said.

“If you don’t feel like you’re a part of the school community, then you’re less inclined to want to be involved with things that might benefit you, like speech and debate, like theater, like [activities] outside of sports,” she said. “The school community loses because we’ve got this wonderful, rich, diverse group that doesn’t want to invest in the school because they don’t feel the school is investing in them.”

Allen, who attended South as a METCO student from 1991 to 1994, said he occasionally received disparaging remarks about his race. His tendency to spend time only with fellow METCO students, he said, limited his social and academic growth and at times made him feel disconnected from the school.

“Being a METCO student, there was comfort being around other METCO students,” he said. “However, I think maybe stepping out of that comfort zone and joining clubs and participating in activities that may not have involved the social circle that I was involved in might have helped with that.”

A 30 percent increase in bus costs this year forced the school to discontinue its 5:15 METCO bus, leaving only the 6 p.m. bus for METCO students with afterschool activities, Sumner said. While this inconvenience did not stop him from participating in football, Gomez said it has prevented others from engaging in extracurriculars altogether, leaving them with fewer opportunities to get involved with the school.

While geographical distance can play a significant role in connectedness with the school, Sumner noted that resident black students are facing comparable challenges to METCO students.

“I am as much concerned, if not more so, about the resident black and Latino kids because I just see this serious stress level because they don’t get to go back somewhere else where they might just be able to breathe; they’re here all the time,” she said. “If you don’t feel like you belong at school and then you don’t feel very comfortable in your neighborhood, how much stress is that?”

While the YRBS indicated a 30 percent gap between black and white student response rates in high school, the disparity among middle school responses was only 5 percent. Sophomore Larissa Williams, who attended Oak Hill, said South’s larger population creates a more separated community, isolating minority students. Leveled high-school classes further decrease classroom diversity, senior Simone Lassar said, noticing that in her experience, higher course level can denote greater racial homogeneity. Turner said the tendency to place students of color in lower-level classes limits their potential.

“Don’t set low expectations for black students,” she said. “Assume that they can handle high-level classes and that they can manage their stuff. They’re not just here to be on a sports team and take all low-level classes that they’re going to pass with easy As.”

Stembridge said the school has looked to increase class diversity by encouraging teachers to recommend more black and Latino students to ACP and Honors classes. Recent professional development meetings among South faculty have also centered around how teachers can best serve all students, he said.

“The challenge that we present with our teachers is we want them to be able to make an individual connection with their students,” he said. “It’s really simply about getting to know the person and finding out what their experiences have been in the past … and what works for them.”

As Stembridge mentioned, the student body and administration have been working to tackle issues of race at South for years. The Black Student Union, whose membership has seen an increase in Latino students this year, offers a safe place to discuss race on local and national levels, co-presidents Turner and Williams said. Courageous Conversations on Race, a student-led group that will visit sophomore chemistry classes this spring, gives students the chance to have open conversations about sensitive topics, teacher facilitator Deborah Linder said.

“A lot of kids weren’t sharing their stories. They were kind of keeping them to themselves,” she said. “By sharing them, they’re allowing other kids to realize that they can come out and share their stories as well. There are things that teachers and students alike do that they don’t realize are making kids feel alienated. … What we need to do is make people more aware of it so that we don’t make those actions or say the wrong things.”

Classes like Leadership and Diversity and African American Literature give students time to ask these difficult questions during the school day, Sumner, who teaches both, said. The Harambee Gospel Choir, discontinued this year due to insufficient enrollment, will return next year under a new name, she added.

Sumner also co-leads the Legacy Scholars Program with science department head Gerry Gagnon. The program, which began two years ago, provides support for high-achieving students of color, and Gagnon said it fosters an important sense of community among these students.

“It’s a way that we can build some internal support system, to build a cohort of kids so that they can see that they’re not the only student who has been successful,” he said. “They might be only one of a handful of kids in their AP class or in their honors class, but there is a large critical mass of students who are African American and Latino who are achieving well here at South, so it’s an effort to address the stereotypes that might be present.”

According to Stembridge, increased faculty diversity has been a major goal since he came to South; however, a lack of teachers of color seeking work in the suburbs has made hiring very difficult. A task force comprised of administrators and teachers from both North and South, he said, will also continue to investigate the implications and reasons behind black students’ falling sense of connectedness to their high schools.

For Gomez, however, reversal of this trend must start with student action.

“It needs to come from the kids,” he said. “They can get all these messages and ideas from the adults and superiors, but it’s up to them to take in the message and interpret it into their own mind and finally do something.”

White students’ tendency to question African American students for spending time together in school presents a unique obstacle for black students, Lassar, a Courageous Conversations on Race student facilitator, said.

“It’s a self-perpetuating cycle in a lot of ways,” she said. “Black students feel unwelcome; therefore, they congregate together and seek comfort from people who have similar experiences as them, and then they get called out on it. I just don’t think that you see that same pattern with other minority groups.”

Williams said breaking this cycle starts with individual accountability.

“This is where we’re going to be for the next four years,” she said. “Try and make it an environment that everybody wants to be in and not just a place that’s good for you. You have to realize that there are other people around you and that you can’t be selfish. … Bettering yourself, making yourself a more open person — it makes the school community a better place.”

Given the current political climate, the future of black student connectedness at South remains up in the air, Turner said.

“South is really at an intersection right now,” she said. “It could take a left and go totally off the scale and down to the ground, or it could go right and create a more diverse and accepting environment. It’s just this point in time. It’s 50-50.”

For Stembridge, the survey calls for the district to double down on its efforts to create a truly welcoming atmosphere.

“I’m taking it to heart,” Stembridge said. “Those are pretty stark numbers; those weren’t close. And I think that indicates to all of us … in this building who care about how other people in the building feel — those numbers say to all of us that we have some work to do.”